Monday BS #8: 18.10.21

Something on randomness, risk and price bias

Monday BSers,

Sometimes Monday BS is replete with fully baked cake ideas, other times I'm still kneading the dough and letting the yeast ferment the sugars. I'm trying not just to lob you ready made morsels, but to challenge and tease out meaning, to bring some fresh perspective. We're learning together and I welcome your comments. If you think I'm talking BS, say so but I'm going to take the risk of looking foolish now and again!

Last week, I talked about ergodicity and oatmeal and, on reflection, was concerned that I left you rather in the porridge, floating in a sweet daze of honey fumes and confusion. So with further thought and contemplation, let's talk further. The essential substance of ergodicity tells us that it is the variability and randomness of human behaviour which means that our real life, everyday systems (e.g. our organisations, government institutions) don't always provide us with fair, transparent and consistent outcomes; unlike, let's say, the toss of a fair coin which has limited, defined rules however you play it. So systems containing defined variables are typically ergodic, while systems without (most of human life as there aren't defined variables to our existence) are non ergodic.

So what? It should make us question, in a world of randomness, how best to survive and prosper. Hindsight bias, survivorship bias and ex-post rationalisation would have you believe the world works in linear ways. Look at the lines of business hagiographies which paint this picture. I don't think it's so and that's indeed unsettling.

Today, I'm also going to talk about the treadmill effect and the Aldi Christmas ad.

Let’s get to it… 👍

1) There's no God in Non-Ergodic

Let's pick up on the idea of linear vs. random games by coming back to the coin toss. Let's set the baseline: an ergodic scenario is when the average outcome of a group equals the average outcome of an individual over time, meaning the average outcome of 100 fair coin tossers will be the same as one individual playing the game 100 times. Over time, the results will be similar since there's no skill or advantage that any one individual can gain. We're all even, it's 50/50 and so we call this an ergodic scenario.

If those individual outcomes were to differ hugely from the randomly distributed set of coin tossers, this would be regarded as a non-ergodic scenario. In this case, we'd assume coins had been tampered with and we'd been taken for a ride. A real life version of that scenario is financial markets, which claim to be ergodic but are in fact not. Indeed, Nassim Nicolas Taleb discusses the randomness of the stock market in book 1 of his Incerto Fooled by Randomness where he discusses 'the back fit logic one always sees in events after the fact.' He shares an amusing anecdote from a TV interview discussing this market randomness during which he says 'people think there is a story when there is none.' To which the anchor immediately interjects: 'There was a story about Cisco this morning. Can you comment on that?'

So what's the sum of this? Where there are defined, contained variables (coin tossing), there is ergodicity. Where this is not so (i.e. most of human life since our existence has no defined variables), we have non-ergodicity. One cannot describe real life in models and probabilities, despite statisticians' predilection. Look at the financial crash of 2008: massive, unwarranted over-confidence in a system loaded with out of sight, out mind variability and tail risk (or black swan). Gerald Ashley discussed our model mania on 'A Load of BS' last week. You might like to explore also Taleb's ludic fallacy which he describes as 'the misuse of games to model real life situations.'

I'll build on the non-ergodicity of financial markets another day and talk about how to win in the casino; indeed how to survive, how to avoid ruin, or what Taleb calls the absorbing barrier. Are you hooked yet?

2) Intellectual freedom

Has COVID made you speed up or slow down? Has it given you perspective on what's really important in life (add other cliché questions as suits)? Are you working and striving harder towards the next milestone, perhaps finally taking that risk which frees you from endeavours which are not true to you; or are you frustrated by constraints the virus has imposed upon you leaving you an anxious mess? End of questions.

Personally, I am all of these states and recognise that contradiction. Am I spending my time enslaved by actions which I kid myself are true to me, bending my values to suit a cause, on a never ending treadmill not quite satisfied with the status quo, constantly seeking the next rush, the jab in the vein to flood the brain? A bit.

This treadmill effect, or referred to as hedonic adaptation, means that when we hit a certain level of achievement, we quickly take it for granted and move to the next target. We become enslaved by this idolatry and are never fulfilled.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau beautifully explained hedonic adaptation in his 1754 Discourse on Inequality with the following words:

“Since these conveniences by becoming habitual had almost entirely ceased to be enjoyable, and at the same time degenerated into true needs, it became much more cruel to be deprived of them than to possess them was sweet, and men were unhappy to lose them without being happy to possess them.”

Aristotle said that a free person is someone who can be free with their opinions, who can say what they think and do what they think is the right thing to do:

“Be a free thinker and don’t accept everything you hear as truth. Be critical and evaluate what you believe in.”

By following societal or economic pressures, one is never totally free. Escaping economic pressure is an ideal, but worrying sporadically about what one's peers think is a road to nowhere.

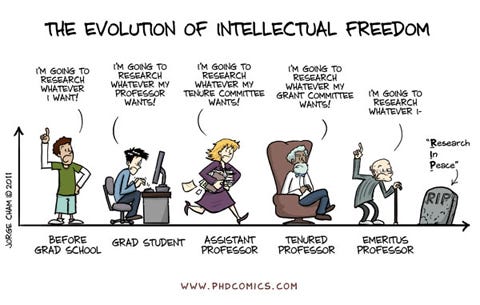

Counter-intuitively, tenured academics are often most guilty of this. You'd think not - tenure means permanency so professors should feel quite free to espouse their wildest opinions. Conversely, academic institutions are highly conformist with few willing to speak against the consensus. (This is exacerbated by the coddling problem which I wrote about in my weekend BS a month ago.)

Why is this? What have they got to lose? Publishing deals, invitations to speak? Small fry compared to the risks many others take in life. They too become enslaved to their profession. No risk, no skin in the game, only upside, nothing to lose.

My conclusion isn't to say we must all quit our jobs for higher purpose; but it is valid to challenge ourselves, and each other, in how much time we spend in self-service (enslaved, don't rock the boat) vs. in more courageous, altruistic pursuits.

3) A Christmas fool

Most of us are susceptible to price quality bias. In other words, we tend to rate similar products more highly as the price rises. Wine is an obvious example we can all grasp onto. In part because most of us have no idea how to judge wine, in part because we don't trust our palettes, in part because wine is enigmatic and, final part, there is some placebo going on. If I spend £100 on a bottle, it will bloody well taste good and equally, if someone offers me a glass from that same bottle, it must also descend the gullet with élan.

As Joe Fattorini and I discussed in the pod, there is endless BS in wine.

This Aldi France Christmas ad of last year is a BS dream (I'm yet to have one) and addresses this price quality bias head on and humorously. It is a delight. Particularly so because our judgements are so heavily affected by brand perception, and it's punishingly hard to change preferences once we're anchored.

Richard Shotton writes convincingly about strategies to release the anchors in The Choice Factory. Life changing events are one of the best times to pounce, so nudge, nudge advertisers if you're reading.

By the way, while sometimes it does make outright sense to be a satisficer and buy Aldi, other times, it's perfectly reasonable to optimise for the very best. As Joe said in our pod, sometimes I feel like a £10 bottle of wine and sometimes I want a £100 wine experience. After £30, there’s not much additional quality one can get into a bottle but the purchase doesn't always have to be economically rational, and that’s fine. Similarly with luxury goods, these are maximiser/optimiser products. One wants the best, or the perception of best, regardless of production costs or prosaic quality comparisons. The pleasure is as much transactional as utilitarian; this is Carl Menger et al Austrian school of economics.

Of course sometimes, counter-intuitively, increasing the price increases sales. If you've ever left unwanted goods outside your house with the sign 'Please take me' and nobody bites, try changing the sign to '£25 for the lot' and you'll find it's get nicked almost immediately.

Till next time.

If you enjoyed this, if you took just one titbit into your Monday morning commute (?), or if you’re keeping back one provocation for your evening pipe, then please share Monday BS with friends.

If you thought this was terrible and are considering leaving for good, why not share it first with your enemies?

Have a great week! 😃

Daniel