Welcome to all new readers of the Paths Less Trodden interview series. Join other smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

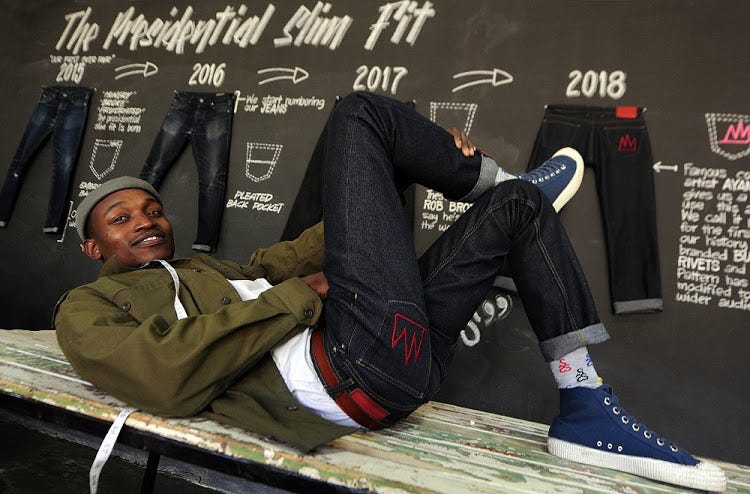

Paths Less Trodden is brought to you by Tshepo, one of South Africa’s most exciting and sought after fashion brands.

Tshepo Mohlala’s story, values and life philosophy are a perfect match for everything that I am striving to show in this newsletter. From the most humble beginnings, Tshepo (meaning hope), the self-taught stylist and designer, has built his business from the ground up, and is recognised as one of South Africa’s hippest denim brands.

He is a born fighter and entrepreneur of the best kind. Follow his rise to international stardom on Twitter and Instagram. Or follow the celebrities and taste makers who love him by checking out the beautiful Presidential Slim Fit jeans here.

Hi friends 😀 ,

In this Paths Less Trodden episode, I talked with ex-England rugby Sevens captain Ollie Phillips.

You can enjoy it now both in written form below and in audio above. Enjoy!

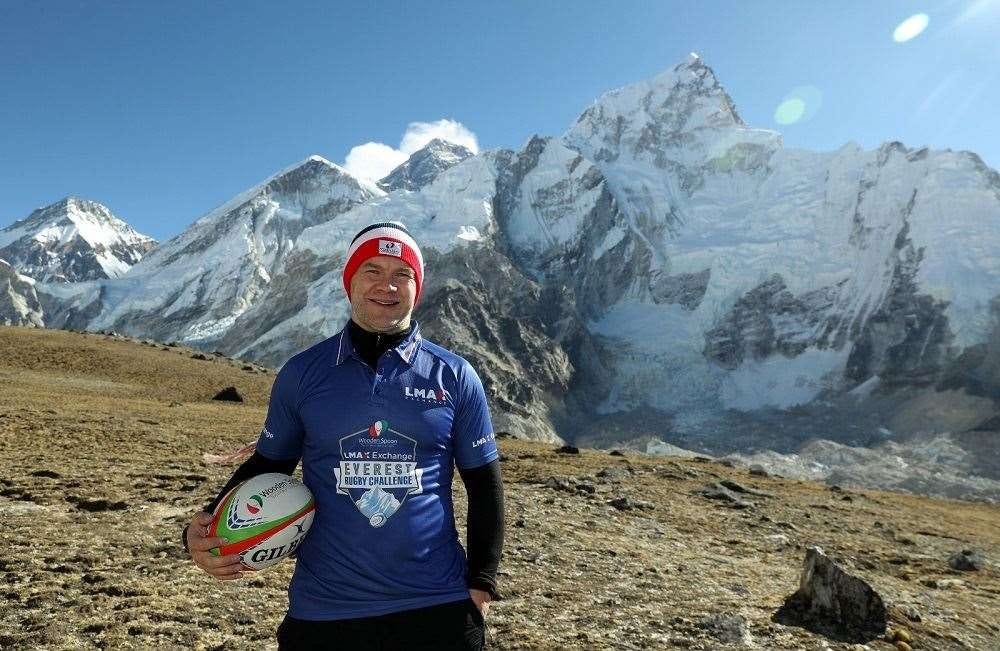

Ollie Phillips is no Nikola Tesla, Leonardo da Vinci, Benjamin Franklin nor Aristotle. One must bring the man down to earth before lavishing too much praise. Reasonably, most of us never hit such polymathic heights, so let’s call Ollie a generalist; and by the way one who has successfully scaled Everest and played rugby on it, so there’s a height the inventor of the induction motor, the founder of the Lyceum and a Founding Father never negotiated.

The warning against being a generalist has persisted for hundreds of years in dozens of languages. “Equipped with knives all over, yet none is sharp,” warn people in China. Many of the most high impact individuals however, contemporary and historical, have been generalists whose lessons Ollie follows, deliberately or otherwise; combining interests to maximise their creative impact.

Ollie captained England Rugby Union Sevens (he was voted best Sevens player in the world in 2009), he is a four times Guinness World Record holder, he is a writer, sports commentator, motivational speaker, fundraiser, adventurer, holder of a Cambridge University MBA and lastly a Director at professional services network PWC (this perhaps the grout holding the prettier tiles in his mosaic career together).

His is not the archetypal professional sportsman’s story. He won accolades and trophies but has also ridden a swerving rollercoaster of self-discovery and introspection. His on field victories speak for themselves but his failings and foibles shine a greater light on his being. His Paths Less Trodden qualification is literal: he has played rugby on Everest, ventured to the North Pole and sailed around the world.

To understand how Ollie rose to the pinnacles of his sport, played for the biggest club side in the world, captained his country but then veered off into addiction and depression, read on…

Rugby is better than tiddlywinks

Ollie’s description of himself as “a short, fat kid who was bizarrely quite fast” conjures cartoonish images of a wind up, rotund Speedy Gonzales astounding rugby teammates and opposition with unexpected endeavours. “I was good at it. I used to score the winning tries so was more inclined to play that than other options like tiddlywinks.” A Darwinian mindset from a young age.

Ollie’s parents divorced when he was ten, splitting the family, and so rugby became his community, an outlet for frustration, an environment where praise and support flowed, a band aid substitute for a father who conferred little emotion and inclined to criticise first, “someone just so disinterested in everything that I'm passionate about, and giving me no recognition and reward every time I seek it.” Where his mother (“a hero”) would think “selling ice cubes in the Gobi Desert a brilliant idea”, rugby granted equilibrium and role models.

It also fuelled an ego whose kindling required regular replenishment. Divorce is common but lack of paternal acknowledgement is harrowing. Rugby was a constant, the highs were addictive but they masked insecurities, they became an adolescent comfort blanket via a rugby scholarship to Brighton College, and they kept Ollie afloat during a 10 year playing career when adoration and self-admiration were in plentiful circular supply. Sport was solace but it was also a dependency, its fealty a great succour.

Forrest Gump, obsessed

An obsession with multiple sports came from the satisfaction that team play delivered and the physiological rush of perpetual exercise. Each athletic discipline was a gateway drug to the next: Ollie captained the school for rugby (playing England Juniors at the same time), he played England water polo, ran and played cricket for Sussex county and played hockey for Southeast England. Worse vices for a teenager but sport was joy mixed with obsession.

“I remember at 16 to 17 when girls were coming into my life, I became very body conscious about getting a six pack. I realise what a load of nonsense now but then it was everything. My Mum would pick me and my brother up from school and I’d throw my bag into the back of the car, put my trainers on and in my full shirt and trousers from school, I'd run home, and I'd race her home. It was about a five, six mile journey but if traffic was bad, well, I’d be home first. I became properly obsessed. If I was going out for drinks, I'd go down to the beach in the evening in my jeans, my jumper and my usual black shoes, but I'd run there so I’d turn up absolutely pissing with sweat. It's utterly ridiculous, right? But I just was obsessed by it, because I love the feeling.”

“Couple that with, I'm good at it. And I enjoy the mental battle. You might be more talented than me but I can outlast you. I've worked so hard to get my level of fitness up that I can be competitive with you.”

The characteristics that hatch winners sit atop the precipice of a sheer drop.

First failure

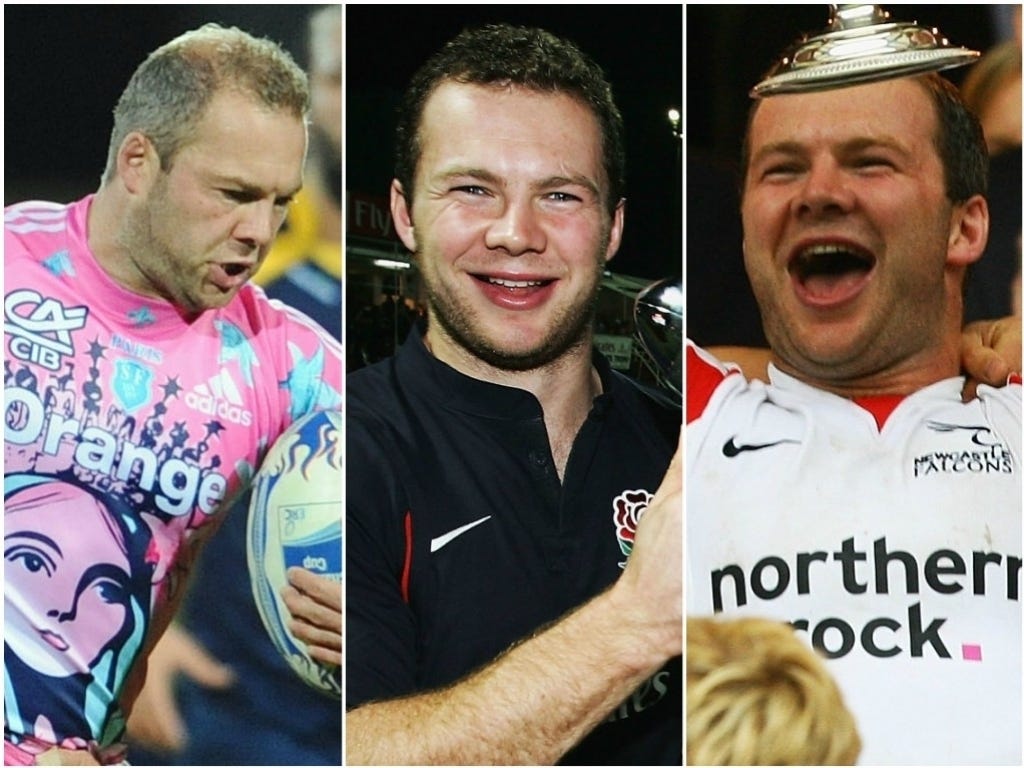

Revelling in recognition and praise, Ollie, in his words, “fucked up my A-Levels, spent too much time on a rugby field chasing skirt.” An unintentional but diverting image of a young man clearly looking to score at all costs. Durham University gave him a lifeline and Ollie collected a fine Business BA while getting in the door at Newcastle Falcons; the natural move.

Best player in the world

The ego had landed but Durham provided direction and stability, Newcastle presented a platform to build a professional career and this ultimately elevated Ollie to captain the England Sevens team, win the Global Sevens Player of the Year Award in 2009 and launch peak period Ollie at Stade Français in Paris, the biggest club side in the world at the time. Here was the opportunity to prove himself further at 15-a-side alongside luminaries like James Haskell, Tom Palmer, Sergio Parisse and Lionel Beauxis. By which time, he had cast off the shackles which inhibited his Newcastle career, a time of self-doubt, burden of error, apprehension for injury and the focus on ‘just getting through it.’ How easily the veneer of fearlessness is scratched.

“I wasted four or five years of my talent at the beginning that I didn't need to. My energy had shifted from enjoying and celebrating my God given talents [to worrying].”

The magical 2009 England year, then signing for Stade Français at 26 flicked the switch and freed Ollie to play his juiciest rugby.

Now I’m speaking your language

So much for the Englishman abroad stereotype, Ollie immersed himself in the French language with great vigour. Learning the language at Stade meant becoming part of the team fabric. “There were lots of people who could speak English, but they didn't want to. And I fucking loved that. It was unashamedly saying, ‘no, fuck you. I'm not going to bother.’ They know I can't speak it but when they see how hard you’re trying, then they love you. Then they welcome you with open arms and the whole city becomes a totally different place; but until you get to that tipping point, it’s a pretty lonely place.” Paris in a nutshell.

The final whistle

“And then it was all over. I was desperate.”

The rugby career ended quite suddenly in 2012 at the World Cup after a calf injury and an avoidable operation which took away the Go-faster sprinting stripes, rudimentary to a winger, especially in the shorter format. Dreams were shattered, withdrawal and denial set in. Ollie explains: “You're obviously seeking that drug again. So first of all, there was massive denial for me. I had a plan to go to the World Cup, to the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow and then to the Olympics in Rio 2016.”

Turbulent waves turned to opportunity soon through an invitation by Sir Robin Knox-Johnston to join the Clipper Round the World Yacht Race; this would become a life changing experience. Even then, Ollie thought he would take a year away from professional sport and return gloriously to playing again – “delusions of grandeur” he says himself.

Ollie imagined sailing as opiate to the drug of professional rugby; status, recognition and reward. Clipper bought into the vision too of “ex-England captain pin-up PR stunt,” their first port of call Rio, his last dance on the Copacabana three years later with World Cup trophy aloft. Doubtless, Ollie would run to this presumptive beach party in full training gear and beat the team bus to it for the endorphin blast.

Right time, right place

The return to rugby was a chimera but Clipper put a match to further feats of daring. The Wooden Spoon charity had picked up wind of the sail and invited Ollie to lead an expedition to the North Pole to set a record for the northern most rugby match in history. Clipper also tacked Ollie to PWC. He met a partner on a leg of the race who was so impressed with his leadership that he as good as hired him on the spot. Take note networkers where the real action is; it’s clearly not LinkedIn!

Father and son nosedive

This phoenix rising from the ashes was synchronous with a nosedive in Ollie’s testy relationship with his father.

“It deteriorated massively. After I retired, I reflected that the only time that my Dad's remotely ever had positive words about my rugby career was when I got voted best player in the world. The other one was when I signed for Stade; because I signed for a lot of money. Suddenly he thought, oh wow, well done son living in Paris.

When I came back from the Clipper race, the relationship totally flopped to the point where we didn't talk and that lasted three years.”

“It culminated in a big ‘Fuck You’ moment. And that's when I went through this journey of depression.”

Despite the afterglow of elite sport opening doors to new ventures, “I totally lost control after the [Clipper] race, because everything that I took motivation from, that gave me security, identity and community was rugby. And that had vanished.”

The rugby artery was severed and Ollie was detached without the game he loved. “The euphoria and excitement of a crowd, being a somebody in the press, with the sponsors, all that vanishes. From the moment you stop, literally, it's scary how quickly it drops. So that hits your ego and your pride.”

The abrupt dislocation, not from a career, but from a way of life, was disorienting, a mental free fall. “What do I do? What value do I bring now?”

Imposter syndrome

Walking into PWC, already as a Director and with an expectant team, was daunting; even for a man who has faced down Jonah Lomu. “I was very technically skills specific. My role was to execute certain things like passing or kicking.”

“I'm walking into an environment where, technically, I'm useless. I've never done it before. I don't know anything about it. I'm surprised I'm still here.”

“I’m meant to be bringing all these softer skills into the environment, but I don't feel like I've got any credibility or any value. I get replies in technical jargon and I’ve no idea what we're talking about. It was a very lonely, bewildering, unsettling place.”

I wondered whether the know-how of playing high pressure sport accords the apparatus and panorama to cope with these new corporate challenges. I believe transfers from club to company work if well engineered, but have lower odds of smooth transition without a drawbridge between vessel and landing point.

“When you dealt with disappointment in your playing career, you were always confident that you’ve got the capability. Okay, this club doesn't like me, or I fucked up in that game. But I know exactly what I did wrong. I know exactly how to put it right. And I still back myself. I didn't have any of this technical competency anymore and I didn't have any clarity about how I build it up. That is unsettling.” Six years in, the “kid in a sweetshop, all nervous energy, desperate to prove myself” has settled, is far more at ease and phlegmatic; a conversion not dissimilar to the mental release on arrival at Stade Français after the Newcastle apprenticeship.

God’s gift learns how to build relationships

Away from work, there were different mental obstacles. With his father’s shadow in the background, adapting to life away from the roaring stadium, Ollie sought refuge in countless, casual, futile romantic flings, chasing repeated affirmation, manufacturing immediate but emotionally hollow highs.

“I met a girl and took her to the Bahamas after two days. My addiction was that feeling that I used to get from sport, you’re selected to play for England, feeling like somebody, feeling recognised, adored, loved, cared for.”

“I got that from women - huge, high intense moments of emotion and connection. I want to feel like you love me more than anything in the world. I needed those big euphoric highs.”

The turning point was a girlfriend’s miscarriage. Ollie had emotionally checked out and she was distraught. He is ashamed of his behaviour. His counselling started to disentangle the post-rugby self-deception: “I was an arsehole, but I was an honest arsehole. So you’re one of seven [girls], but I’m telling you the truth, so that’s fine.”

It took his now wife Lucy to break the spell. Formerly one of the ‘seven’, she booted him into touch and he respected her for that. In his gut, he knew she was right, she was the soul mate he’d been looking for.

Ollie has continued his therapy, unscrambling his need for recognition and reward. An athlete craving the limelight is not uncommon, but in this case, a filial chasm aggravated the itch. Today, Ollie is a family man with three children, he has reconciled himself to a manageable, if one-dimensional, paternal relationship. And right now, the only Guinness on his mind is more world records.

Quick fire

What's the kindest thing anyone's ever done for you?

“Giving me their time”

What’s your most powerful memory?

“My Grandma dying”

Tell us something interesting about yourself most people don’t know

“My nickname is Brad Pig. When I was 17 at school, when you get the new influx of sixth formers, we'd all gone out and a girl came over and said, ‘Oh, are you Ollie Phillips? I've heard so much about you. I heard you look like Brad Pitt.’ And I was like, boom, boom! Yes, of course I do. And then I turned out for rugby training the next day with all the school lads and we're on the bus to go and play a game. ‘Lads you're never going to believe this. This girl last night, she came up to me and said I look like Brad Pitt. Their response: ‘more like Brad Pig.’ Then when I was at university it became Pumba. In my professional career, when I was 21, everyone used to think I looked about 51, so my nickname was Benjamin Button.”

Which book do you gift most regularly?

“Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert Kiyosaki”

What's your desert island music?

“Anything Van Morrison”

Winding down away from work, tell me about your hobbies

Anything physically active I just revel in. Which is one of the things I worry most about now post my playing career because my body is starting to fall apart on me. I want to make sure that I can carry on doing those things because it’s so important for me and my own mental health. And equally I want to be able to do it with my kids.”

I hope you enjoyed this interview. Please add your comments below, and help spread the word by sharing this post with others you think would like it. Thank you! 🥳

Next time, I will be sharing the story of James O’Malley who spent 15 years in the Royal Navy:

Leading counter-piracy operations in Somalia on behalf of the European Union

Leading a major project dealing with the Ebola crisis

Working as EU medical operations planner in volatile situations in Iraq, the Far East and Afghanistan

He recently led an expedition to Everest where he suffered a collapsed lung and nearly lost his life. Subscribe here to make sure this story lands in your inbox!

Share this post