Monday BS #10: 01.11.21

On success, learning lessons and honesty

Monday BSers,

Today’s edition comes to you from Exmoor on the Somerset/Devon borders. Breathe that clean air! From Dubai last week, this could hardly be more different.

More importantly, I’m excited to share my first guest post on Monday BS by Pete Weishaupt, a member of the early stage seed investment fund Social Leverage based in Arizona, US. I’ve come to enjoy Pete’s writings on subjects ranging from writing, technology, entrepreneurship and indeed some BS too.

Do follow him on Medium and Beehiiv.

And then more from me on failing to learn from lessons and stealing at work. Let’s get to it. 🏇

If you haven’t got A Load of BS in your life yet, please subscribe here:

Guest contribution by Pete Weishaupt

1) Behaviour Before Success

In a discussion with Tom Bilyeu, Trevor Moawad relayed a story his father told him about one of the most successful magazine entrepreneurs in the world. The man was failing out of high school and struggled growing up. He was raised by a single mom in the Midwest. He promised his mother he’d take the SAT test. He didn’t expect to get a good score.

His score came back. He got a 1480 out of 1600 on the SAT. His mother, knowing her kid, asks, “Did you cheat?” He swore to her he didn’t cheat. In his senior year he realizes he’s smart and decides to attend classes. He stops hanging out with his old crowd. The teachers and kids seemed to notice. They started treating him differently.

He graduates, attends community college, goes on to Wichita State, and eventually to an Ivy League. He later became a successful magazine entrepreneur.

You say to yourself, “He’s smart. He just needed the standardized test to unlock his potential.” No. This isn’t the story. What comes next is the important part.

12 years later this man gets a letter in the mail from Princeton, New Jersey. He doesn’t think anything about it. The next day his wife asks him if he’s going to open the letter.

He opens it. It turns out the SAT board periodically reviews their test taking procedures and policies. He was one of 13 people sent the wrong SAT score. His actual score was 740.

People say his whole life changed when he got the 1480. What really happened is his behaviour changed. He started acting like a person with a 1480 and started doing what someone with a score like that does.

Trevor says language is powerful, but your behaviour is way ahead of your success. The lesson is, in addition to language, how you feel about the past shouldn’t determine who you are in the future. The keys are language and behaviour. You can view the entire conversation below.

2) This time it isn't different

Simple systems with little variability are very predictable (e.g. tossing a fair coin endlessly will not produce random results on average). When human behaviour gets involved, we no longer understand all the differing variables. Life, thankfully, is not as trivial or binary as a coin toss.

Mostly everything we do and experience hides unlimited alternative histories and it might make us reflect that our real control over events and outcomes is far more random than ex-post narrative.

Our refusal to accept this is related in repeated financial market crashes; the proponents of the stock market crash of 1987, the Great Bond Massacre of 1994, the Asian crisis of 1997, the tech bubble burst in 2000 and the worldwide financial collapse in 2007 all, in advance of disaster, claimed that 'this time it was different' despite recent history telling them that if you continue to spin the roulette wheel with a growing pile of chips, eventually you will blow up.

There are a couple of things going on here. Firstly, we suffer from terrible optimism bias; as we overestimate our abilities, we become more susceptible to believing sycophants and 'yes men', and so believe more in the quality of our plans and the likelihood of their future success. I posed this problem to Marc Ross in our conversation last week on political power and influence and asked him how we protect against those in positions of power from taking risky decisions which may be based on false assumptions.

The answer to that question is the roommate of the above 'firstly'. It's about skin in the game. It's far easier to be over-confident and take outlandish risk if you suffer no downside risk. To misquote Nassim Taleb analogously, if you're committed to intervening in Libya on the basis that you're happy to relocate there yourself in the aftermath, then please be my guest.

Survival matters more than performance. The best start-ups or investments are just the ones who are able to survive. It's not the fastest skiers that become world champions, but the fastest amongst those who survived. It's a lesson worth remembering when we hear the masters of our universe presenting well-constructed, intellectual arguments that 'this time it's different'.

3) 'I always show staff how to put their fingers in the till'

I started thinking about honesty after reading an article by James Timpson, the CEO of Timpson, a chain of shoe and watch repairers in the UK. He recognises that there will always be a small minority of employees who will steal from the firm and to counter it, "we tell our colleagues the best ways to steal from us. It sounds counterintuitive, but if everyone understands that we know how it works, they’re less likely to do it in the first place." Rather than spending disproportionate time trying to catch culprits or accepting it as a cost of doing business.

This got me thinking further about honesty in the workplace; or moreover our definition of it.

After the Enron scandal in 2001, academics On Amir, Nina Mazar and Dan Ariely addressed the question of honesty and identified two types.

"One is the type of dishonesty that evokes the image of a pair of crooks circling a gas station. As they cruise by, they consider how much money is in the till, who might be around to stop them, and what punishment they may face if caught."

"Then there is the second type of dishonesty. This is the kind committed by people who generally consider themselves honest - the men and women who have 'borrowed' a pen from a conference site, taken an extra splash of soda from the soft drink dispenser or falsely reported a meal as a business expense."

Stand up (sheepishly) if you recognise yourself in type 2. This cost the US economy c. $600bn vs. $525m for type 1 in 2004. No reason to assume these numbers are lower today, although it's actually the delta that is most striking here.

Well, it's not really cheating is it...?

Ariely and co sought to test their type 2 hypothesis in what become a well-known 2008 experiment at Harvard University. The results corroborate the hypothesis in spades.

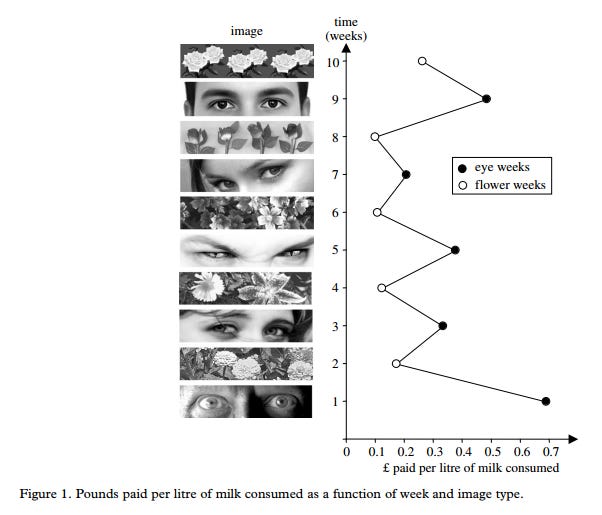

A corollary of this is perhaps part of a (unlikely) solution. In the video below, Daniel Kahneman highlights an experiment at a UK university café where students pay into an honesty box.

Posters were placed above the box, alternating between eyes and flowers, and you see clearly in the results table how much people paid as the images alternated weekly. What's so fascinating is that people are barely aware the posters are there nor that they influence their behaviour.

Maybe as a means at least to keep the stationery budget in check, offices might paste the eyeballs of the CEO at strategic points of human weakness. That'll get us running back double quick. Not me guv...

Till next time.

If you enjoyed this, if you took just one titbit into your Monday morning commute (?), or if you’re keeping back one provocation for your evening pipe, then please share Monday BS with friends.

If you thought this was terrible and are considering leaving for good, why not share it first with your enemies?

Have a great week! 😃

Daniel